Introduction

A deep understanding of Kautilya’s Arthashastra is essential for studying ancient Indian political thought. Among the most detailed and systematic works in political science from the Vedic civilization, Arthashastra transformed politics into a structured discipline. Kautilya used scientific methods and practical observations to evaluate political theories, making him one of the earliest political realists in history.

Kautilya served as the chief advisor to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya from 317 to 293 BCE. He was renowned for his intelligence and detailed discussions on governance, warfare, social order, diplomacy, ethics, and statecraft in Arthashastra. The Mauryan Empire, under his guidance, was more extensive than British India, spanning from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas and reaching as far west as Iran. Following Alexander’s departure, Magadha emerged as the dominant kingdom in India, with Kautilya playing a crucial role as an advisor to the ruler. He is also known as Chanakya or Vishnugupta (c. 350–275 BCE).

One of Kautilya’s most influential concepts in statecraft is the Mandala Theory. This theory of international relations suggests that a state’s allies and enemies depend on their geographical position relative to the ruler. While the origins of this idea remain unclear, it is not found in early Vedic or Brahmin texts but appears in the Manusmriti and Mahabharata. Kautilya elaborated on this theory extensively in Arthashastra, making it a pragmatic and timeless framework for understanding interstate relations and ensuring a state’s security.

Mandal Theory Explanation

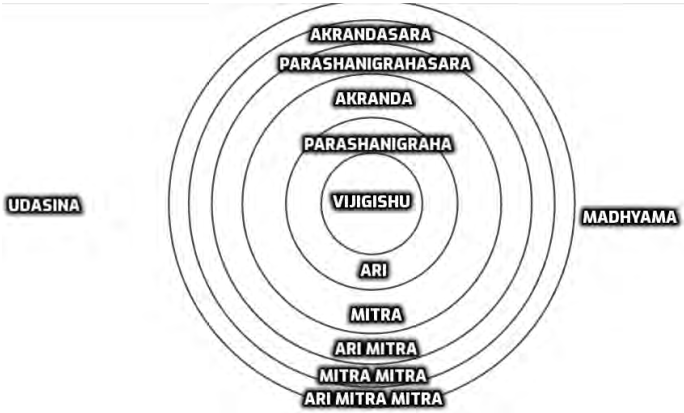

“Your neighbor is your natural enemy, and your neighbor’s neighbor is your friend.”

This principle forms the foundation of Kautilya’s Mandala Theory. The term mandala, meaning “circle” in Sanskrit, represents the network of relationships between states. In Arthashastra, Kautilya introduces the Mandala system to explain foreign relations and strategic alliances. He advises that a ruler seeking territorial expansion must balance alliances and enemies to maintain control. Smaller states should align with others of similar status to safeguard themselves against stronger, expansionist powers.

Kautilya’s Mandala system consists of 12 types of kingdoms, each playing a distinct role:

- Vijigishu (The Conqueror) – The central ruler aiming for expansion. While the focus is on one Vijigishu, any powerful king within the Mandala with similar ambitions could hold this title.

- Ari (The Enemy) – The immediate neighboring state, which is considered a natural rival. Kautilya classifies enemies into three types: Prakritik Ari (natural enemies), Sahaj Ari (rivals from within the same lineage), and Kritrim Ari (artificial enemies who oppose for political reasons).

- Mitra (The Ally) – The state neighboring Ari. Based on the idea that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” Mitra naturally supports Vijigishu. Allies can be categorized as Prakritik Mitra (bordering states), Sahaja Mitra (related by blood or kinship), and Kritrim Mitra (states seeking protection).

- Ari Mitra (Enemy’s Friend) – A state that aligns with Ari, making it a potential threat to Vijigishu.

- Mitra Mitra (Friend’s Friend) – A state allied with Mitra, and therefore, a natural supporter of Vijigishu.

- Ari Mitra-Mitra (Friend of the Enemy’s Friend) – A state supporting Ari Mitra, effectively an opponent of Vijigishu.

- Parshnigraha (Rear Enemy) – A kingdom positioned behind Vijigishu, posing a strategic threat.

- Akranda (Rear Ally) – The state behind Parshnigraha, supporting Vijigishu.

- Parshnigrahasara (Rear Enemy’s Ally) – A kingdom backing Parshnigraha, indirectly opposing Vijigishu.

- Akrandsara (Rear Ally’s Friend) – A state that supports Akranda, and thus, Vijigishu.

- Madhyama (The Mediator State) – A central power balancing conflicts between Vijigishu and Ari. It must be strong enough to influence both sides when needed.

- Udasina (The Neutral State) – A kingdom that remains neutral in conflicts but must be more powerful than Vijigishu, Ari, and Madhyama combined.

The Mandala Theory represents an early model of international relations with remarkable complexity. Despite being formulated over 2,000 years ago, its structure remains relevant. Kautilya outlined a six-fold foreign policy for dealing with neighboring states, including peace, neutrality, alliances, strategic maneuvers, aggression, and warfare. He also recommended five key diplomatic strategies: conciliation, bribery, division, deception, and direct attack.

Kautilya emphasized pragmatism over moral considerations, stating:

“A king should not hesitate to break alliances that prove disadvantageous.”

His theory revolves around power, strategy, and conquest, encapsulated in his belief that “power is the possession of strength.”

Contemporary Relevance to India

While Kautilya’s Mandala Theory may not fully apply in modern geopolitics, its principles remain significant. At both regional and global levels, international relations still involve strategic alliances and rivalries. Whether consciously or not, many nations continue to follow his military and diplomatic strategies.

Technological advancements and new defense systems have changed the nature of warfare, yet the core of Kautilya’s ideas remains relevant. The tensions India faces with neighboring countries such as Pakistan, China, and Bangladesh illustrate the ongoing importance of geopolitical strategy. Kautilya’s approach is based on logical assessments rather than emotions, reinforcing the idea that diplomacy should prioritize national security. He famously stated:

“A king who understands diplomacy can conquer the world.”

This does not imply perpetual conflict but underscores the need for a vigilant and proactive foreign policy.

Conclusion

Kautilya remains a foundational figure in political realism, offering a clear framework for power dynamics, diplomacy, and governance. His Mandala Theory provides strategic guidelines for world conquest and survival in a competitive international landscape. He methodically analyzed power struggles and exposed the realities of international politics, where the strong dominate the weak.

Unlike idealists, Kautilya was not concerned with reputation or morality but rather with effective governance and strategy. His geopolitical insights continue to hold value in today’s interconnected world, where national interest, alliances, enmity, and diplomacy remain as relevant as ever.

Understanding ancient Indian political philosophy is incomplete without Kautilya’s insights into interstate relations, making his contributions vital even in the age of global diplomacy.